A reflection from December 16, 2019 by John Rutter

[Ken Gray] It is now ten years since the death of Sir David Wilcocks, organist, conductor, composer/arranger, and college administrator.

One of my great pleasures as a student at the Royal College of Music from 1977-1979 was singing in the RCM chorus which Sir David conducted . The repertoire was brilliant: Bach, Eight-part motets; Faure, Requiem; Walton, Belshazzar’s Feast; a shared performance with the London Bach Choir at the Royal Albert Hall of David Fanshawe’s African Sanctus; and the best of all, the Britten War Requiem with Peter Pears as the soloist.

Years later, in Victoria he was guest conductor for a concert week that included a Bruckner Mass; Palestrina, Missa Papae Marchelli; Howells, A Spotless Rose; and the Rutter Gloria.

Sir David’s role as an administrator is often ignored. It is fair to say that he transformed the college from a latent Victorian institution to one well able to embrace and engage the classical music world in the late 20th century.

Two of my organ teachers, Hugh McLean and Richard Popplewell worked closely with Sir David over the years. While students at Clifton College, Bristol Sir David and my Victoria piano teacher, Charles Palmer, studied music under the legendary Douglas Fox. In these and other settings I saw him in both gracious acts and fierce condemnation — His brilliance and passion for perfection were unrivaled. I once auditioned for a chamber choir he assembled in 1979. As I lacked both of the above, my audition was unsuccessful.

I am pleased to share the reminiscence below by John Rutter. May it bring good memories to those of us who had the privilege of working under Sir David’s direction.

[John Rutter] I had heard of him, of course, long before I met him. David Willcocks was a revered figure in choral circles ever since he took over from the ailing Boris Ord in 1957 as organist of King’s College Cambridge and director of its renowned choir. His career had, in a sense, come full circle: in 1939, as an outstandingly gifted musical teenager at Clifton College, he was awarded an organ scholarship at King’s but was commissioned into the Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry after only a year. Following distinguished war service—he was awarded the Military Cross in the Normandy landings—Captain Willcocks returned to King’s in 1945 to complete his three-year term of office. Appointments as organist of Salisbury Cathedral (1947–50) and Worcester Cathedral (1950–7) followed, but it came as no surprise when he was called back to King’s, and by the time I reached my own teens, he had turned an already fine choir into a world-renowned one.

We all listened to the annual Christmas Eve Festival of Nine Lessons and Carols on the radio, and marvelled at the unfolding series of Willcocks King’s recordings which began in 1960 with an album of Bach motets. In the following year he co-edited (with the Bach Choir conductor Reginald Jacques) the first of the Carols for Choirs books, an anthology which transformed our musical celebration of Christmas with the first of David’s own magical descant versions of the great Christmas hymns and his refreshing, exquisitely voiced arrangements of traditional carols.

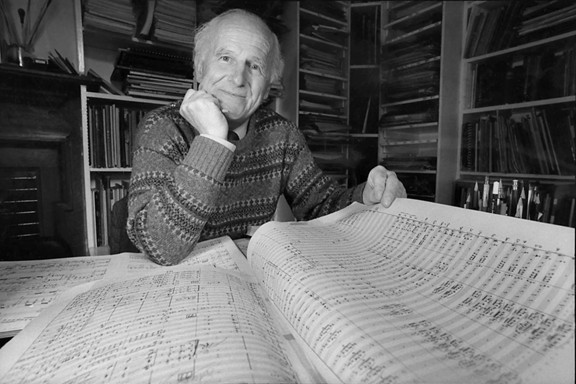

David Willcocks and John Rutter

Aware of his stellar reputation, I was overawed when I was assigned, in my second year at Cambridge, to his weekly harmony and counterpoint class. He generally hastened into the classroom one minute before the appointed time, a wiry, slender figure quivering with energy, who got straight to grips with, say, a canonic Bach chorale prelude that we were expected to complete given only the first two bars. His daily schedule was, I later realised, impossibly crowded during those years, and when the hour was up he generally sped away to his next appointment, but one day he took me aside and said ‘I understand you’ve been composing, Mr Rutter – would you bring some of your work to my rooms in King’s at nine o’clock next Monday morning?’ That was an order, not a suggestion, so I punctually appeared the next Monday with a small bundle of manuscripts (including, I recall, the Shepherd’s Pipe Carol). My palms damp and my mouth dry, I stood in his elegant rooms overlooking King’s meadow awaiting his verdict as he leafed through the pile. He looked up and said ‘would you be interested in these being published by Oxford University Press?’. David was for many years the OUP advisor for church music, and to be offered a place in the same catalogue as Vaughan Williams, Walton, and indeed Willcocks, was an enviable opportunity.

David took my manuscripts away with him—Monday was the day when he spent the afternoon at OUP headquarters in Conduit Street and the evening rehearsing the Bach Choir (by now his choir, following the death of Reginald Jacques)—and two days later I received a letter on OUP’s impressive crested writing paper not only accepting my pieces for publication but offering me an annual retainer of £50 (it later rose slightly) in exchange for first refusal on future work. I hope I thanked him properly, because he was the reason I made the massive leap from aspiring composer to published composer.

That was in 1966. A little later, as a shamefully unmotivated PhD student but increasingly committed composer, I became David’s unofficial assistant, spending more time helping him with musical chores such as part-copying, orchestrating, and infilling of sketchy Willcocks scores than I ever did on my research. In 1969 he invited me to co-edit the second (orange) volume of Carols for Choirs, and collaboration ripened into lifelong friendship. I learned many lessons from him by example: perfectionism, attention to detail (he was a crackshot proof-reader), leadership, willingness to work exhaustingly long hours without weakening, the psychology and technique of training and conducting choirs, and above all the value of life itself and the crime of wasting any of it. David loved life, probably because he had witnessed so much tragic loss of it in the war, also, perhaps, from the loss of his son James at the age of 33 from cancer. David’s career was long and full, from organ scholar to cathedral organist, King’s choir director, principal of the Royal College of Music, and, in a happy final chapter, freelance conductor equally willing to work with skilled professionals or modest amateurs.

King’s College Chapel, Cambridge

He was unassuming about his composing and arranging, but could undoubtedly have made it his principal focus had he so chosen. Everything he wrote (including the iconic descant to O come, all ye faithful, scribbled on a train journey) met an exacting standard of craftsmanship, and his Christmas music still lights up the sky. Quite a legacy in itself, but we must add to that the new standards he set for choirs everywhere: King’s College Choir under DVW was an exemplar, a yardstick, a benchmark. Quite simply, that choir made choirs everywhere else sing better. Finally, in David’s centenary year, we must remember that he was a great teacher, mentor and inspiration: those who sang under him, worked with him, learned from him, or just met him, have gone out into the world and inspired others, as he inspired them. I am immensely the richer for having been his student, assistant, and friend.

Visit the takenote.ca HOME page for a colourful display of hundreds of other blogs which may interest or inspire you

Leave a comment