He told us and we should have listened. Certainly Americans (and to some extent Canadians) should have taken seriously the evolution of anti-black racism into a more widespread and broadly targeted anti-immigrant BIPOC ideology. Man of us continue to scratch our heads wondering where the energy for the growing hatred originates. It is much more than job insecurity for whites. It is fueled by INCEL anxiety especially amongst male voters in both our countries between the ages of 20 and 35. According to the late Leonard Zeskind who has studied far-right movements throughout North American for decades, we should have paid attention to the many warning signs. We could have, and should have, placed these cultural concerns on a very public stage and educated each other about our history and our possible future. We might have been able to head off what is now an escalating Xenophobia now driving deportations without due process, weaponizing U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement officials, and stripping agencies abroad including USAID of their ability to exercise compassion in a vulnerable world.

Again, I ask, what is the source and energy for such hateful action? And next, what can we do now to resist and recover what little generosity is left? The notes below are extracted from Leonard Zeskind, Who Foresaw the Rise of White Nationalism, Dies at 75 by Trip Gabriel, New York Times, April 24, 2025.

With Blood and Politics, Leonard Zeskind predicted that anti-immigrant ideologies would become part of mainstream American politics, and warned about downplaying the threat.

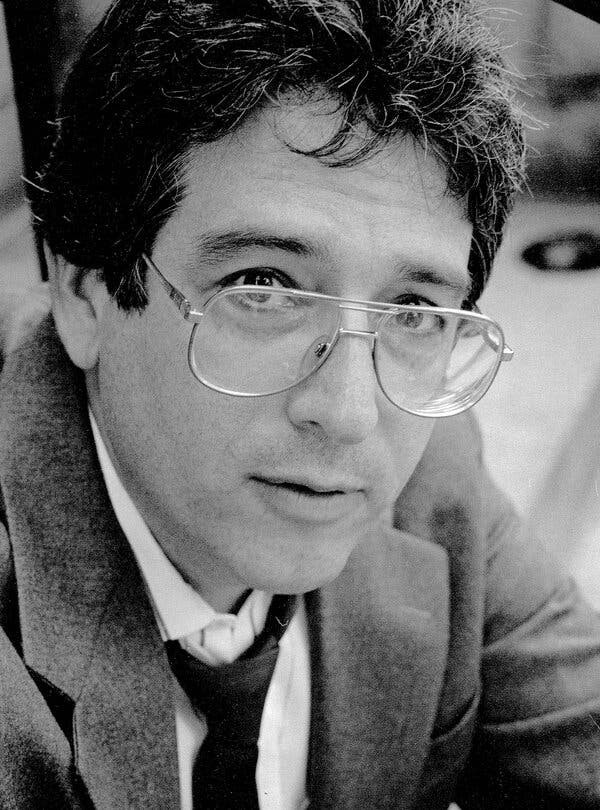

Leonard Zeskind, a dogged tracker of right-wing hate groups, who foresaw before almost anyone else that anti-immigrant ideologies would move to the mainstream of American politics, died on April 15 at his home in Kansas City, Mo. He was 75 . . .

Long before Donald J. Trump’s nativist rhetoric in 2023 accusing immigrants of “poisoning the blood” of the United States, Mr. Zeskind, a single-minded researcher, spent decades studying white nationalism, documenting how its leading voices had shifted their vitriol from Black Americans to non-white immigrants.

His 2009 book, Blood and Politics: The History of the White Nationalist Movement From the Margins to the Mainstream, resulted from years of following contemporary Klansmen, neo-Nazis, militia members and other right-wing groups . . .

“For a nice Jewish boy, I’ve gone to more Klan rallies, neo-Nazi events and Posse Comitatus things than anybody should ever have to,” Mr. Zeskind said in 2018.

Recently, “Blood and Politics” was one of 381 books removed from the U.S. Naval Academy library in a purge of titles about racism and diversity ordered by the Trump administration.

One of Mr. Zeskind’s central themes was that before the 1960s, white supremacists fought to maintain the status quo of segregation, especially in the South. But after the era of civil rights victories, he maintained, white nationalists began to see themselves as an oppressed group, victims who needed to mount an insurgency against the establishment.

Their principal adversaries were immigrants from the developing world who were tilting the demographics of the United States away from earlier waves of Northern Europeans.

Despite the subtitle of Mr. Zeskind’s book, asserting that white nationalists had moved “from the margins to the mainstream,” many reviewers in 2009 were skeptical, treating his work as a backward look at a fringe movement led by racist crackpots whose day was over. The United States had just elected its first Black president, and extremist movements such as Christian Identity, which preached that white Christians were entitled to dominate government and society, seemed antiquated.

The Los Angeles Times waved away those hate groups as questing after “an impossible future.” NPR noted that “while a handful of bigots” were still grumbling about the South’s defeat in the Civil War and spreading conspiracies about Jews, “some 70 million others have, in a testament to the overwhelming tolerance of contemporary American society, gone ahead and elected Barack Obama president.”

Mr. Zeskind insisted that white nationalists should not be underestimated, and he was especially concerned about their influence on Republican politics.

He identified those influences in the candidacies of David Duke, a former Klan leader who won a majority of white voters when he ran for statewide office in Louisiana in 1990, and in Pat Buchanan, who fared well in G.O.P. presidential primaries in the 1990s, running on a platform of reducing immigration, opposing multiculturalism and stoking the culture wars.

Mr. Buchanan’s issues offered a template for Mr. Trump, who leveraged similar ideas to wrest control of the Republican Party from its establishment.

Mr. Zeskind spoke about Mr. Trump in a 2018 town hall speech in Washington on the one-year anniversary of the march in Charlottesville, Va., by young white supremacists, whose zealotry the president had minimized. Mr. Zeskind said that Mr. Trump hadn’t created an upsurge in hatred of non-white people — he was a product of it.

“White supremacy and white privilege have been dominant elements of our society from the beginning,” he said. “It breeds a whole set of behaviors in people, and it should be deeply and widely discussed in every level of our society.” [. . .]

At [a] 2018 town hall meeting in Washington, Mr. Zeskind called on Democrats in Congress to vehemently oppose a little-noticed bill sponsored by Representative Steve King, Republican of Iowa, to end birthright citizenship, the post-Civil War guarantee that anyone born in the United States is a citizen. The cause had become a focus of anti-immigrant groups warning of threats to the “white race.”

“They want to smash up the 14th Amendment,” Mr. Zeskind said, addressing Democratic officials, “and I think you guys should scream about it.”

The following year, in an article in The New York Times about how Mr. King, a backbencher in his party, had anticipated many of Mr. Trump’s anti-immigrant stances, the congressman said in an interview, “White nationalist, white supremacist, Western civilization — how did that language become offensive?” Republican leaders in the House stripped Mr. King of his committee assignments over the remark, and he lost re-election in 2020.

But the issue did not die. One of President Trump’s first moves in January was an executive order to end birthright citizenship. Last week, the Supreme Court agreed to hear arguments over Mr. Trump’s order.

Leave a comment