Photo by Daan Huttinga on Unsplash

[Ken Gray]

With thanks to Jesse Zink for this book review I thought something completely different from the geopolitics of the past few days was in order. I really enjoyed the book and would love to see the movie if ever produced. Highly recommended.

[Jesse Zink]

How do you live when the future seems so bleak, fearful, and uncertain?

This, I think, is the question facing everyone alive today as we stare down a climate emergency, democratic decay, and societal fracture. In my recent book, Faithful, Creative, Hopeful: Fifteen Theses for Christians in a Crisis-Shaped World, I engage this question in dialogue with the book and movie The Children of Men and write about what it means to live with hope and confidence when that seems so questionable and foolish.

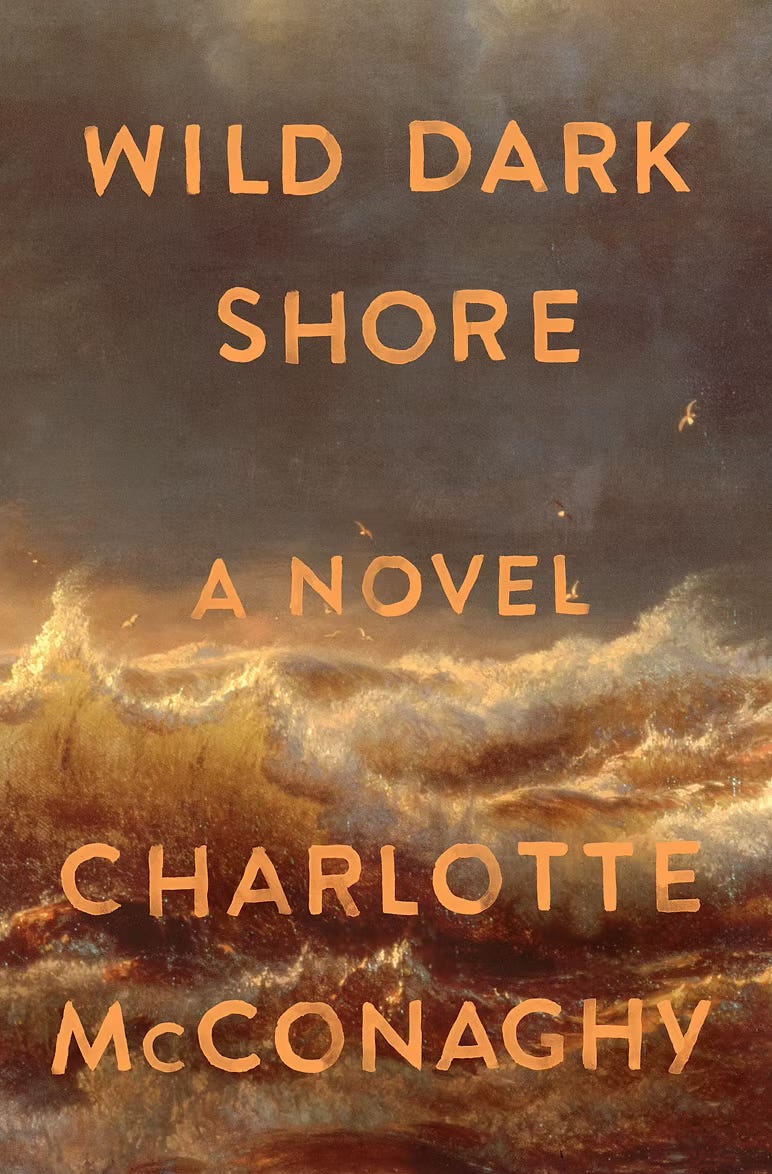

Charlotte McConaghy’s new book Wild Dark Shore addresses this same question and arrives at a beautiful answer. The book is set on the fictional Shearwater Island (based on the real life Macquarie Island), halfway between Tasmania and Antarctica. The only remaining human residents are the Salt family—father Dominic and his three children Raff, Fen, and Orley—who are the caretakers of what once used to be a scientific research station and seed bank (modelled on the seed vault in Svalbard that I’ve always wanted to visit). This is a book that is all about the future—or, rather, the deep dread that comes from uncertainty about the future.

Future Uncertain

On a macro level in this novel, the sea level is rapidly rising and beaches and animal habitats are being wiped out. That’s part of the reason why the Salt family are to be evacuated from the island in just a couple of weeks. It’s been decided that the seed bank—which is meant to endure long into the future, safe from harm—is being closed. There’s only space to remove half of its millions of seeds, which means that whole species of plants will be lost forever to rising seas. The sense of an imperilled future is dramatized in the book by the steadily rising water levels in the entrance to the seed bank, which is supposed to remain dry. On a micro level, the Salt family, who has lived on the island for eight years, has great questions about its future and how a move back to the mainland will affect them. This uncertainty is being played out in significant tensions and relational damage within the family.

The book starts with a woman—Rowan—washing ashore after her boat wrecks. Rowan has basically given up hope on the future. She had spent many years building the home of her dreams in a rural part of Australia and connecting with the land there, only for it to be completely destroyed in a recent wildfire. This experience and others has convinced her that she never wants to have children, which is told in flashback conversations with her husband, Hank, who does want children. Since the fire destroyed her home, she has basically given up on doing anything because she’s given up hope in the future. At one point she tells Dominic the story of building her house: “It’s all I did. Backbreaking labor for years and years. I had this insane drive to build a house that would keep my sisters safe. But it was stupid, and I’m sick of trying to make things that will survive this world because nothing can, anymore.” (p. 122)

But there are subtle signs of a future-orientation throughout the book. There is ample description of the penguin and seal colonies on the island and we learn that they had nearly been wiped out by westerners in the 19th century who exploited them for their oil. But their ongoing presence is an implicit testimony to the ability of the natural world to rebound from human devastation. Seeds—and much of the book is about saving seeds—are all about the future. At one point Dominic refers to the seeds as “this last floundering hope.” (p. 10)

To relate or not to relate, that is the question

The other overriding theme in this book is the relatedness—or lack thereof—of life, human or otherwise. For those who have given up on the future—represented by Rowan—relationship with others is dangerous. This is represented by her unwillingness to have children, which she tries to explain to Fen at one point.

“It’s not a good idea to fall in love, okay? Not with people, and not with places. I loved a landscape and watched it burn. This island… you can see it disappearing. There’s no stable ground. Not here. Not anywhere else. What that instability does to relationships—what constant danger does to them—is devastating. It’s unraveling.” (pp. 88-89)

But the presence of the natural world keeps reminding the reader of the importance of relatedness, notably in a relationship between a mother and child humpback whale. In addition, at one point we hear the voice of the scientist in charge of the seed bank who has been told the seed bank is shutting down and they can only keep half the seeds so preserve those that are good for food. The scientist fumes that:

“it was utter stupidity. Short-sighted, linear thinking. The world, he tried to explain, needed biodiversity more than it needed any other thing….And still, he had to decide on half. Which means that when the fires rage and the seas swallow and the bombs destroy, there will be no backups for the thousands and thousands of lost species. No way to replant. They will simply be gone forever.” (p. 94)

This is obviously true, by the way. How can you save the plants that are good for food, without also saving those needed for pollination?

Relatedness in spite/because of uncertainty

The reason I found this such a genius novel is that it weaves together the two central concerns of this day and age—our anxiety about the future and our approaches to relationship with others. When we are anxious and fearful about the future, it is a natural response to want to cut ourselves off from relationship with others. This is what Rowan initially represents. But what the logic of the natural world teaches us is that the fullness of life comes from relationship with other human and non-human life, even and especially when the future seems in question. It is precisely because we are so uncertain about the future that we should relate to one another more deeply.

I don’t want to spoil this story too much more, so I’ll just note these few things. The arc of the plot—which is gripping, in a kind of mystery-thrillish way—focuses on Rowan who comes face-to-face with the shortness of the future on Shearwater Island but also realizes how deeply she wants to be in relationship with others, in this case the Salt family. In different moments, she forms deep connection with Dominic and his three children, with a wonderful Eucharistic-type scene to culminate it all in which relationships within the Salt family that had been difficult or attenuated begin to be repaired.

The consistent theme of the story is that in the face of destruction and uncertainty, the answer is relationship with one another. The sea level rises quickly and the seed vault is being destroyed and it’s clear they can’t even save half. The whole family and Rowan work on rescuing what they can and at one point Rowan looks around at the Salts and her new love for all of them and thinks “for the first time in a long while I see a future.” (p. 237) Dominic at one point says, “Maybe we will drown or burn or starve one day, but until then we get to choose if we’ll add to that destruction or if we will care for each other.” (p. 257)

The end is, of course, for you to discover (I’ll only say it’s a John 15:13 moment). Towards the end of the book Rowan reflects on her life thus far and how she was wrong on one major thing, “something so deeply wrong I am stunned I ever believed it: that in the face of world’s end love should shrink.” (p. 290)

Toward hope

In my chapter on hope in Faithful, Creative, Hopeful, I write that hope comes from three steps: living without regard for ourselves but for others; bearing witness to the pain of the world; drawing close to others in self-surrendering love. We can only do this, I write, when we believe—however fragile our belief—that there is a future. This, I write, is a description of the ministry of Jesus of Nazareth. It’s also what happens in The Children of Men. And it describes the Salts and Rowan on Shearwater Island.

The speed and scale of climate-induced destruction in Wild, Dark Shore is rapid and terrifying. This is a bleak book. But it is also a profoundly hopeful one. We live at a time in which there is so much pressure on us that results in our individualization and our atomization. When there is so much fear about the future that may seem a logical response. But it’s not the right one and it’s not a sustainable one. The response to our insecurity is to draw closer to one another and form deep relationships to help us all collectively sustain the pressure of this time. It won’t surprise you for me to say that I find this in the life of the church. But I am grateful for this novel that demonstrates so vividly how we can seek the good life and live in hope in the face of the uncertainty of what is coming at us.

Visit the takenote.ca HOME page for a colourful display of hundreds of other blogs which may interest or inspire you.

Leave a comment